The Google-Bomb That Went Undetected

Can a page rank for keywords in a redirected domain name? There is evidence to support this theory. Find out more here.

I was asked to work on a legal case earlier this year involving two finance companies. One of the companies was accused of trademark infringement by the other, and the defendant’s website suddenly started ranking for the plaintiff’s service mark.

The only issue was that the specific phrase had nothing to do with the defendant’s website. I’ll talk about a unique feature of Google’s ranking algorithm in this article.

What I expected to find for this situation was very unique in relation to what I at last found. The majority of search ranking factors are very easy to understand.

In SEO, explanations are typically formulated using the logical principle of Occam’s razor, which states that “the simplest explanation is usually the right one.”

For instance, if a page ranks for a particular keyword, the keyword will be included in the HTML code of the page, such as the title, body text, and image alt text; failing that, the keyword may be included in links to the page.

However, this was to be a one-of-a-kind instance in which there was simply no media linking the distinctive, brand-name phrase.

The case summary

In a number of ways, the situation was quite unique.

The plaintiff had come up with a catchphrase a few years ago that they used to promote their business in traditional media.

The expression joined a word firmly connected with their business and items with a word that was not generally connected with their industry.

They failed to advance the expression on the web, and as it was extremely special, there were less pages that showed up in Google query items for the exact question.

When you searched for the catchphrase, the results showed 1.7 million pages, but many of them were only partial matches. When you searched with quotes around the phrase, the number of results dropped to just over 3,000.

Since the term was commonly used in a different industry, the majority of the exact-match results related to that other use.

The plaintiff’s website had the expectation that only their website would appear in search results when the phrase was searched upon, and some of their pages contained the catchphrase.

The plaintiff put out ads in offline media outlets, and they ended their radio ads by saying something along the lines of “For more information, search in Google for _!”

Sooner or later, they, at the end of the day, looked for “_ _” and thought it was a little odd that the respondent’s site showed up on page one, close to the lower half of the principal page of indexed lists.

They didn’t give it much thought at the time because their own website was at the top of the results.

However, they came to the conclusion that they might want to get their catchphrase registered as a.com domain name. They were dissatisfied to learn that the domain had already been registered.

When they entered the domain, the URL took them to one of their closest rivals, who was in their area and only a few miles away.

That’s when they hired an attorney and decided to sue.

I was pretty sure I would find them a real “smoking gun” to explain the unjust ranking when the attorney asked me to investigate how the defendant’s website began ranking for the plaintiff’s catchphrase.

In my experience, for keyword text to appear prominently in the rankings for that keyword query, it must be associated with a webpage in some way.

I assumed that the defendant’s website’s code would contain keywords, hidden or otherwise, or links with anchor text directing to the webpage. A page ranking for synonym searches for a keyword is another possibility.)

The website’s code did not contain the keyword.

I first did a spot check on the page that was in the rankings; neither the page nor its code contained the keyword.

I looked at duplicates of the page in the Web File’s archive of memorable duplicates of site pages, and I didn’t find the watchword present in the page’s code.

To be careful, I fostered a rundown of the multitude of website pages’ examples in the Web Chronicle, and I set up Shouting Frog Web optimization bug to creep every one of them and to check for the watchword in the pages’ code.

In any of the older versions of the page, I was unable to locate the keyword. That surprised me a little bit because the person committing trademark infringement in some cases can be quite naive or brazen.

Then, I figure out where they intentionally harmed registrations of domain names. They could very well have connected better with the marks of their rivals by employing hidden keywords.

However, none of the thousands of copies of pages in the Internet Archive contained the keyword.

The backlinks also did not contain the keyword.

Then, I concluded that it had to be in the anchor text of the backlinks. If external links containing the term have been developed, it is possible for a webpage to have no keyword at all and still rank highly for the keyword. I checked the backlinks with Majestic and found no links with the keyword.

Surprised, I was at this point. In most cases, a website cannot rank for terms that are not present on it or in the anchor text of its backlinks.

If the keyword phrase is found in the text of a page that is linking to the one in question, one of the conditions is met. In most cases, the keyword must dominate the page’s overall subject matter in order for this to occur, or else one would expect the keyword to be very close to the link.

Since there is only a tenuous connection between the keyword and the anchor text, one would expect the relevancy to be minimal. This is also harder to find because industry link research tools can’t tell because the connection is so weak.

Another situation in which the keyword was present on the page (and/or on pages linking to the one in question) for some time before being removed is one that I have seen a few times.

I see this in cases involving online reputation management in which a defamatory reference was present and we later persuaded (or compelled) a webpage to remove defamatory links or content.

You might be surprised to learn that Google’s algorithm sometimes keeps keyword associations with webpages even after they are deleted. This is called “historical keyword association.”

However, following the removal of the keyword association, the page typically begins to recede from the search results fairly rapidly in most instances. The association between the keywords appears to last much longer in some cases.)

What relationship did cybersquatting have with the webpage’s ranking?

You probably know where I’m going if you’ve read this far: the cybersquatting of the space name that got going this claim.

Indeed, this is my direction. In fact, the letter sequences used to create four domain names were confusingly similar to the plaintiff’s trademark. The client’s brand name followed this structure: ” The “Unique” Business

As a result, “The” was the first word in the phrase, followed by a “unique” word that had nothing to do with the industry and the final “industry” word, which is very common in that niche of the finance industry. The phase as a whole was unique.

The following methods were used to create the four domain names, with spaces added for readability:

- The [Unique] [Industry] . com

- [Unique] [Industry] . com

- [Unique] [Industrys] . com

- [Unique] . [Industry]

The entire trademark word phrase with the spaces removed was the first domain, followed by.com.

The initial “The” term was removed from the second domain, which was identical to the first.

The industry term was made plural with the addition of an “s” at the end of the word preceding.com on the third domain, which was identical to the second.

One of the new generic top-level domains (New gTLDs), in which the industry term serves as the TLD, was utilized for the fourth domain, as shown in Example. Finance.

I approached a few respected SEO colleagues privately, and to a man, they all stated that a link between keywords in the domain names was extremely unlikely, if not a very weak relevancy signal.

One of them sleuthed to find a professional resource page where both the offended party and the respondent were recorded, some distance separated on the page, alongside addresses and connections to their individual sites – expressive text for every business recorded on the pages included notice of the offended party’s expression.

But was this really the reason?

Other businesses were also listed on the page, and the catchphrase was significantly closer to the plaintiff’s website link. Their websites did not appear in Google’s results for the term “searches.”

This response was extremely unsatisfactory due to the fact that co-mentions on the same directory page typically do not result in the websites of one’s competitors ranking for one’s trademark name search; however, perhaps this extremely weak connection could be an explanation.

I began to consider the possibility that the defendant’s website’s first-place ranking in Google’s rankings for “[Unique] [Industry]” was due to the four infringing domain names that were redirected to the defendant’s website.

The four domain names were the primary link between the defendant’s website and the keyword term. Evidently, this theory is influenced in part by the issue of whether Google uses keywords in domain names.

Google uses keywords in domain names, or not?

It has long been known that properly constructed keywords in URLs convey keyword relevance to pages.

In 2009, former Googler Matt Cutts stated that keywords in URLs aid “a little bit” provided that keyword stuffing is avoided. Even now, “Use words in URLs” is a recommendation from Google’s SEO Starter Guide.

Domain names, on the other hand, are very specific parts of URLs. Over time, there has been an unsettling shift because many in the industry noticed that keyworded domain names seemed to have been given too much weight.

In 2012, Google made a concerted effort to lessen the influence that exact match domain (EMD) names had on the rankings for their equivalent keyword queries. The effect of the EMD update was to lessen rather than eliminate the expectation that HumptyDumpty.com would rank highly for searches involving “Humpty Dumpty.”

Google has recently emphasized that keywords in URLs have little effect once the page they are associated with is indexed.

Google has downplayed the influence of keyword URLs because many websites have lost rankings and traffic by converting from abstract URLs to keyworded URLs, which requires more resources than a reasonable return on investment. Since transformation to keyworded URLs changes expects time to restore rankings with the all-new resultant URLs, losing watchword positioning history benefits.)

Keywords in domain names continue to have an impact, despite the fact that the weighting of the EMD keyword relevancy factor has been decreased and the influence of keywords in URLs and domain names has been downplayed.

In addition to the keyword’s presence in a domain name, the domain name itself frequently serves as the anchor text for links to it, which may increase or decrease the domain name’s keyword relevancy.

The effect of the keywords in the domain name and the anchor text of external links pointing to the domain become increasingly difficult to distinguish.

In any case, keyword-rich domain names have an obvious advantage in search engine optimization.

Either Google uses keywords in domain names when determining rankings, or the closely related anchor text in links to the domain gives the domain an advantage in rankings for its own keywords.

The fact that keywords in domain names are definitely a factor that enables webpages to rank for searches for those keyword queries means that the distinction between those two things may not matter.

The next question is whether the redirection of the infringing domains could transfer the keyword relevancy to the URL they were pointed to because the keywords associated with those domains are influential in search.

Why do we use redirection?

The next question that needs to be asked is whether a domain’s keyword relevancy is transferred through redirection, even though keywords in domain names and links unquestionably have some ranking advantage for their equivalent or similar search queries.

A redirect is the process of changing a website visitor’s request to view a different page to a different internet address (a webpage URL).

For instance, assuming a web client clicked upon a connection on a page that highlighted “http://example.com”, that page could be set to consequently divert the client to an alternate URL, for example, one at “http://destination.com”.

The process of redirecting URLs on the internet is analogous to setting up a phone number to route calls to a different number.

You may be aware that when a website visitor visits a legacy URL for content that has since been moved, redirects are set up to help them get to the content they want.

When businesses rebrand, they frequently implement a redirect, which necessitates a change in their domain names.

For instance, Overstock.com changed its name to “O.CO” in 2011, believing that the shorter brand name and URL would be more effective. They also changed the URLs for their domain name “overstock.com” to the equivalent URLs for “o.co.”

With this change, customers who typed in or clicked on legacy URL links could be automatically taken to the new URLs if they had bookmarked the old URLs or were more familiar with the old homepage address.

Domain names can also be redirected so that customers can get to a company’s website if they type a URL wrong or if a brand has different spellings when people type it in.

Several of these have been set up by Google; for instance, entering “googel.com,” “gooogle.com,” or “googel.com” into the address bar of a web browser will send you to the official “google.com” domain.

Redirecting domain names is another way to build on or maintain a brand’s goodwill.

For instance, FedEx merged Kinko’s services under its FedEx brand at the beginning of the 2000s. Even now, almost 20 years later, the domain name “fedex.com” is set to redirect to “kinkos.com.”

Because Kinko’s was a well-known brand, the FedEx company is still able to protect its intellectual property by redirecting the domain name. In most cases, trademarks must remain “in use” in order to maintain their registration status. Redirection might be one way to prove that a trademarked name is still “in use.”)

Can a separate webpage rank for a domain name’s keywords in a redirected domain?

Because there isn’t a lot of specific documentation from Google or anyone else, some of my coworkers didn’t think this could affect rankings.

However, there are some intriguing clues that point to the possibility of a dynamic in which rankings for specific keywords are influenced by keywords in a domain name.

First, there is the dynamic that is very similar to it and about which we know a lot: the “Google bombing.”

In 2004, SEO pranksters caused the White House’s biography page for President George W. Bush to rank for the query “miserable failure,” which led to the most famous Google bombing.

This was made possible by a large number of people working together to create external links with the anchor text “miserable failure” and all of them pointing to the biography page for the White House.

The effort resulted in the page ranking for words that were not included in the webpage’s code.

Google bombing works because Google’s algorithm thinks that the text of the link is more about the page it points to than the page it is on. Thus, the page being linked to receives the keyword relevancy signals from the link’s anchor text.

“Does Google transfer keyword relevancy from a redirected URL to the destination URL?” is our inquiry here.

There is evidence to suggest that they do. According to Cutts in 2009,

“Anchor text typically flows through a 301 redirect.”

Additionally, the most recent Google documentation states:

“Ranking signals, such as PageRank or incoming links, will be appropriately transmitted across 301 redirects.”

This is maybe yet unsatisfyingly obscure. According to the colleagues I questioned, this was typically restricted to ranking weight, more commonly referred to as PageRank, rather than any other signals.

Or, it could be that this only applied to the anchor text of links that were redirected to Google; there were no other ways that keywords could be linked to a page URL that was redirected. And in this context, what does the term “appropriately” mean?

Since there was no other content specifically associated with the redirecting domains in the case I was working on, there was no need to transmit any anchor text.

The keyword relevancy that was applied to the defendant’s URL was most likely derived from the keywords themselves, which are present in the domain name.

Therefore, the question also arises as to whether or not keywords in domain names are utilized by Google as a covert ranking signal for keyword relevance.

Cutts stated twelve years ago that “keywords in a URL” have an impact and that the domain is a part of the URL, but this is not clear.

Cutts made it clearer a few years later that Google did pay some attention to keywords in domain names and that they were adjusting how much weight they gave to them.

Prior to that point, having an exact match domain, or “EMD,” for a keyword phrase seemed to indicate a significant capacity to rank for searches involving the phrase. As a result, it was a significant advantage.

Yet, Google distributed an update that renounced a ton of this intrinsic benefit, especially for inferior quality sites.

Those of us in the industry who have been around for a long time are aware that this factor was significantly reduced from what it once was, so it seems likely that Google did not completely remove its influence on that signal.

Obviously, Website design enhancement industry master books and guides have long prompted that web crawlers use watchwords in areas as positioning elements.

In addition, research conducted in the industry has demonstrated a strong connection between having keywords included in domain names and ranking well for those keywords’ queries.

Keywords in a domain name may confer relevancy in searches for related keyword queries, at least based on search engine history.

As this functionality occurs for the anchor text in redirected links, there is reason to believe that this ranking factor could also transfer through a redirect to a destination URL.

What transpired in the case of cybersquatting?

In most cases, we should take it for granted that a page does not rank for a keyword search if the keyword does not have any connection to that page.

Rankings on Google are not based solely on keywords. The catchphrase didn’t appear to be anywhere on the website.

Although a page can rank for synonyms, I can assure you that this keyword has no semantic connection to any of the defendant’s website’s words.

Based on the industry term in the catchphrase, it might have made a partial match, but many other local or national businesses should have also been on page one.

The keyword might have been added to the webpage and then taken out without a copy being saved in the Internet Archive.

However, this seems unlikely given that the catchphrase would have to have been there for some time. Additionally, the keyword is absent from Majestic’s historical backlinks.

One colleague with whom I shared information about the case discovered that, in addition to the redirecting domain names, there was only one thing linking the defendant’s website to the catchphrase.

Both businesses were listed on the same “top 10 provider” Yelp page, but they were not in close proximity.

Could the defendant’s website be considered relevant in a search if keywords are present on the same page as a link to it? Possibly.

However, this appeared unlikely without a closer proximity to the link.

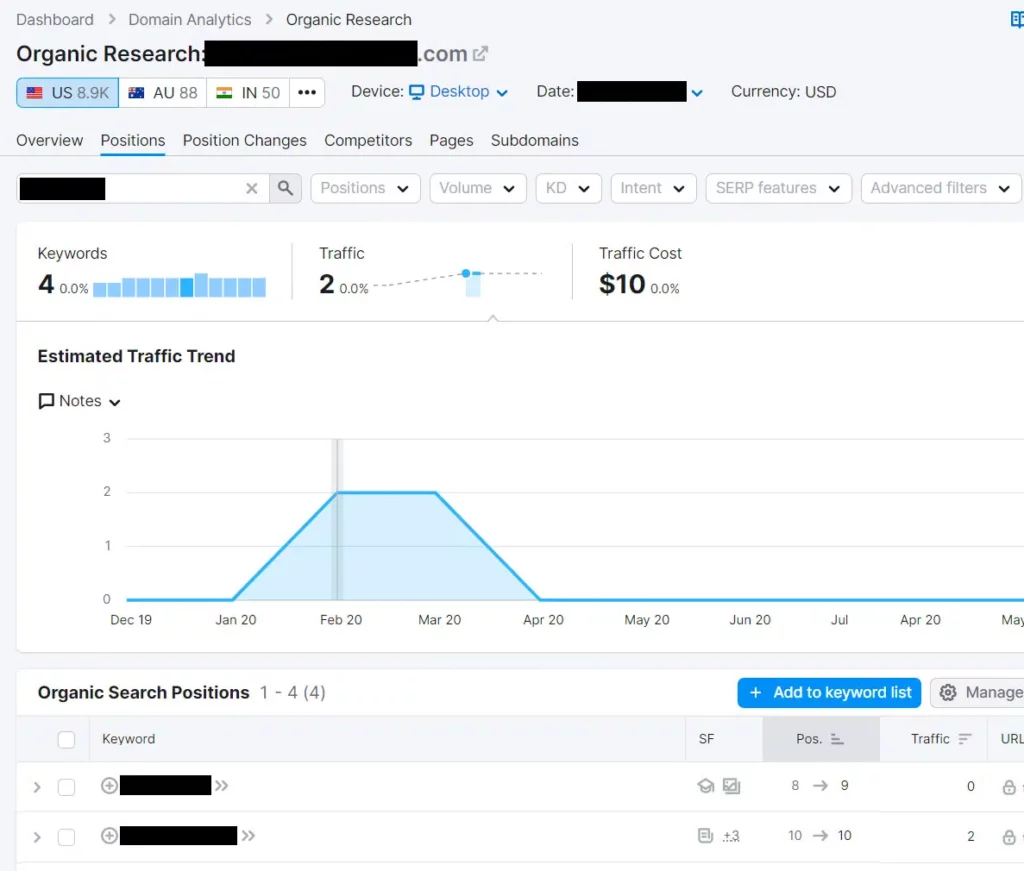

Semrush demonstrated that the defendant’s website abruptly began ranking for catchphrase searches at the beginning of the year, in the same month that the domain names were registered:

I concluded that the most likely explanation for the website’s prominence during a period of time when the trademark was searched was the redirected domain names.

The reason why the website was able to appear for a phrase that was not present appeared to be the spike in Semrush for the catchphrase that occurred simultaneously with the registration and redirection of domain names.

The catchphrase is a kind of niche search phrase, even with the plaintiff’s media advertising.

According to Google Trends, searches for the phrase started when the plaintiff started using it, but the volume is relatively low:

Keywords in a domain name, especially if redirected, might not give much weight to rankings, as you might expect. That, in my opinion, is the case.

Since the catchphrase was not used in a lot of online media, the following other items ranked on the page:

- coincidental matches in which the phrase was used casually or generically in one or two other states.

- or accidental in the sense that the unique term and the industry term happened to be in close proximity to one another.

Nearly any other website would have surpassed the defendant’s website if there had been more content that used the catchphrase.

That website showed that it did not rise very high because it only appeared near the bottom half of the search results page.

However, despite the fact that the facts establish a circumstantial case that the trademark phrase ranking was achieved through cybersquatting and domain redirection, this is not necessarily evidence that this is the case.

Using the scientific method, we can only say that the condition appears to support the theory; however, when dealing with Google, there are still intriguing alternate explanations.

I decided to test the theory as a result.

Experiment: Can a page rank for keywords in a redirected domain name?

I would attempt to create a phrase that had very few pages that would be relevant to the phrase in search results because I wanted to imitate the main conditions of the legal case.

The crucial parts of the phrase in the legal case were a real word that had nothing to do with their industry and a word that was frequently used in their industry.

I came up with the phrase “supercalifragilistic seo” for my test. There are a few SEO-related websites that include the word “supercalifragilistic” on one of their pages, but not necessarily in the same sentence as “SEO.”

Using this phrase, I registered the following domains:

- supercalifragilisticseo.com

- supercalifragilistic-seo.com

- supercalifragilisticseo.agency

- supercalifragilisticseo.media

- supercalifragilisticseo.xyz

I registered these domains with 301 redirects to point to argentmedia.com, the homepage of my agency website.

I submitted each domain name to Google Search Console to have them spidered in order to expedite the experiment.

Even though there was no evidence that the defendant in my legal case had done this, the nature of the internet may have made it unnecessary. Numerous websites use the domain name system (DNS) to automatically generate content.

Profile pages with information about registered domain names, such as WHOIS data showing registration information, are generated automatically by these websites. Additionally, they frequently incorporate additional data, such as:

- The location of the website’s IP address.

- On the same server, additional domains.

- information retrieved from the domain’s homepage.

- Links to statistics about the domain or website from third parties.

- plus more.

It’s possible that Google finds the domains through these everywhere autogenerated domain profile pages.

Having said that, Google itself is a registrar that has access to all new registrations for domain names. Alternately, since they have general access to the internet’s DNS, they could send Googlebot to any registered domain names.

There are instances in which the autogenerated domain information pages lack direct links to the domain names they document. They simply list the space names out in unlinked text.

Google, on the other hand, is able to identify hyperlinks in non-linked text, so even that is not necessarily a barrier.

Non-linked hyperlink mentions have been referred to as “inferred links” by some, but Google representatives have stated that they do not use them for ranking purposes.

However, Google may still use unlinked hyperlinks in text for URL discovery without granting the links any PageRank, so this possibility remains open.

As a result, the infringing domain names in my case may have been discovered by Google as a result of these pages, which could have an impact on the defendant’s website rankings for the trademarked term.

ArgentMedia.com began ranking for the search term within a few weeks of setting up the experimental domain names and redirecting them to my website, but only when the term was actually searched for in quotes: SEO that is supercalifragilistic.

In addition, some of the automated domain profile sites showed up in the results, like the page from “com.all-url.info” in the screenshot above.

At the time this article was written, my website only ranked for the exact-match phrase when the search was done with quotes.

I anticipate that this indicates that Google considers my website to be only marginally relevant to the search term. Due to the small number of webpages that correspond to that specific query, it may only be displaying that result in the list.

Due to the presence of both words in the webpages’ visible text, there are numerous other webpages that more closely match the query when searching without quotes.

Conclusion

My hypothesis that redirection transmits keyword signals appears plausible.

Because it is not possible to separate the influence of keywords found in the domain name from keyword anchor text that may be appearing out there in relation to automatically generated domain profile websites or scraper websites, the precise mechanisms involved remain somewhat hazy.

Intriguingly, a single additional historical event further establishes the redirection of keyword signals. Do you remember the Google bomb calling President Bush a “miserable failure”? In an effort to disperse the bomb, Google finally got around to reducing the White House page’s rankings in searches for “miserable failure.”

However, after Obama was elected, the IT staff at the White House redirected Bush’s previous profile page to Obama’s new one.

Redirecting the URL reversed the “miserable failure” Google bomb suppression because the URL is used as a unique identifier in Google’s ranking suppression and content removal processes for search.

As a considerable lot of the connections highlighting Bramble’s previous memoir page contained the “hopeless disappointment” anchor text, the watchwords then, at that point, became diverted to Obama’s new page, in the long run making it rank for “hopeless disappointment” too. This is yet another example of how keyword data is transmitted via redirection rather than just rank weight alone without any other signals.

Other than exposing a potential vulnerability that could be exploited by the subsequent evolutionary level of a Google bombing prank, demonstrating this particular dynamic in Google’s algorithm does not appear to provide any useful benefits.

Be aware that using this method as a Google bombing could be considered a black hat SEO strategy.

This may indicate that Google has discounted most or all of the keyword ranking advantage that was once inherent in exact match domain names. Any ranking advantage that this might convey appears to be very, very weak.

Due in part to the fact that domain profile websites appear to be deemed extremely low-quality or even spammy by Google, the automated nature of the benefit appears to be negligible.

Although I did not test it with much larger numbers of keyworded domain names, I think that adding hundreds of domain redirects linked from a lot of low-quality domain profile websites might even result in a penalty.